That strangers may not loose their road and have it to goe back againe

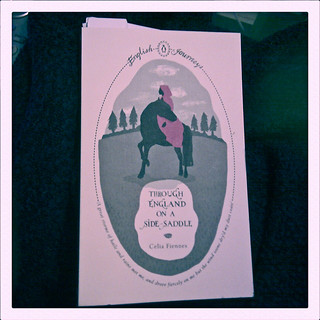

Through England on a Side-Saddle

by Celia Fiennes

I picked this up in a rare glow of national pride, what with certain sporting stuff going on. It’s an odd little book. Published as part of Penguin’s “English Journeys” series, it’s an extract from the 1698 travelogue of a rich Englishwoman travelling on horseback up to Newcastle and down to Cornwall. Intrepid, I think the word is.

The language takes a little getting used to. Not that the words are unfamiliar, but Penguin has left the original spelling and grammar in place, with only the occasional translation in square brackets. It’s jarring but once in the flow I found myself surprisingly able to cope with the same word being spelled three different ways within a paragraph!

This travelogue was written up later from a detailed journal that Fiennes kept on the road, and it suffers a little bit from listing the same few facts about each place: number of churches (I love that this was a reasonably reliable indicator of population!), distance in miles, quality of roads, major trade. But even these facts were sometimes fascinating: in 1698 Liverpool was so small it had only one church! Compare that with Newcastle-upon-Tyne (5 churches) and Bristol (19 churches and a cathedral) – even Wells, now England’s smallest city, had 2 churches and a cathedral! Also, roadsigns were a brand new idea:

“they have one good thing in most parts off this principality [Lancashire] that at all cross wayes there are Posts with Hands pointing to each road with the names of the great town or market towns that it leads to, which does make up for the length of the miles that strangers may not loose their road and have it to goe back againe”

(I so badly want to take a red pen to that now!)

More importantly, Fiennes has occasional flashes of wit and humour that make the drier sections worthwhile. Take, for instance, her comments on St Winfreds Well:

“its a cold water and cleare and runs off very quick so that it would be a pleasant refreshment in the sumer to washe ones self in it, but its shallow not up to the waste so its not easye to dive and washe in; but I thinke I could not have been persuaded to have gone in unless might have had curtains to have drawn about some part of it to have shelter’d from the streete, for the wett garments are no covering to the body; but there I saw abundance of the devout papists on their knees all around the Well; poor people are deluded into an ignorant blind zeale and to be pity’d by us that have the advantage of knowing better”

Fiennes is travelling alone, with local guides (and, I suspect, luggage carriers) in each region. She at no point refers to being a woman travelling without husband or other family, which perhaps is a product of her being rich and well-connected enough that she knows people all over the country (and often describes their houses and gardens lengthily, another bit I found tedious). She makes a point of learning about local trades and industries, going into surprising detail about methods of coal mining, for example. She does, however, show a certain snobbery and prejudice, particularly towards the Scots when she briefly crosses the border:

“those houses are all kinds of Castles and they live great, tho’ in so nasty a way…one has little stomach to eate or use any thing as I have been told by some that has travell’d there; and I am sure I mett with a sample of it enough to discourage my progress farther in Scotland; I attribute it wholly to their sloth for I see they sitt and do little”

Overall I would say this is a fascinating historical document more than a good piece of writing but I am still interested in seeing what else is included in the “English Journeys” series.

The Journals of Celia Fiennes first published 1947 by the Cresset Press.

This selection published 2009 by Penguin Books.

Celia’s one of my heroes. She actually, amazingly visited every county in England during her lifetime but because she was ‘only a woman’ no one realised until hundreds of years later when someone tried to work out why she’d visited one of the last counties late in life, when they checked they realised it was one of the she’d not been to and she’d basically been ticking it off the list! I agree her style is really dry and repetitive but I still rather admire her determination. 🙂

Alex Definitely sounds like she was an amazing woman. And she wasn’t writing for publication so it seems a little unfair to judge her style too harshly.