It is far safer to be feared than loved

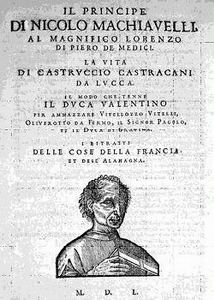

The Prince

by Niccolò Machiavelli

translated from Tuscan Italian by N H Thompson

I find military history tedious so this wasn’t the most fun read for me but it’s a classic and it’s only 99 pages so I figured I’d give it a go.

The premise is that Machiavelli wrote this as a textbook for a member of the powerful Medici family and indeed it is formally dedicated to one of them, but it’s unknown if it was ever read by any Medici or even if that was the true intention.

The book is split into short chapters, each of which is a self-contained essay. The first half of them look at types of prince and types of situation whereby a prince might take over a new military history. The second half looks at the qualities a prince should have and the ways he should behave. There’s extensive use of historical examples, many from Italy but also from all over Europe and occasionally further afield.

To be honest, for all the negative reputation of Machiavelli, this is in general sensible or at least realistic-sounding advice. It is sometimes ruthless but not as much as I had expected at all.

“He who innovates will have for his enemies all those who are well off under the existing order of things, and only lukewarm supporters in those who might be better off under the new.”

“The ruler is not truly wise who cannot discern evils before they develop themselves, and this is a faculty given to few.”

“As long as neither their property nor their honour is touched, the mass of mankind live contentedly, and the Prince has only to cope with the ambition of a few.”

Of course, there is an awful lot of focus on war, which I didn’t like too much and objected to morally. Really much of the first half was a struggle against boredom.

“War is the sole art looked for in one who rules…when Princes devote themselves rather to pleasure than to arms, they lose their dominions.”

However, to make up for the objectionable war focus and dull military history there were moments of fascinating philosophical language and that ratio really flipped in the second half, with a lot more commentary on human nature. I especially liked the reference to Chiron the Centaur (a character I learned about in Song of Achilles) as the perfect instructor to teach princes how to use both the natures of man and beast.

“The manner in which we live, and that in which we ought to live, are things so wide asunder, that he who quits the one to betake himself to the other is more likely to destroy than to save himself; since anyone who would act up to a perfect standard of goodness in everything, must be ruined among so many who are not good. It is essential, therefore, for a Prince…to have learned how to be other than good, and to use or not use his goodness as necessity requires.”

The most famous chapter in the book is “Of cruelty and clemency, and whether it is better to be loved than feared”. But the answer given to that choice is not as clearcut as I often see quoted. As with most chapters, there is the ideal answer and the likely compromise. A prince “should desire to be counted merciful and not cruel” but should accept the reputation of cruelty “where it enables him to keep his subjects united and obedient”. And the famous line in this translation reads “it is far safer to be feared than loved”, which is not quite the same as saying it’s better. Indeed, Machiavelli goes on to caution that to inspire fear should not equal inspiring hate. In fact, there’s a whole chapter devoted to evading contempt and hatred.

There’s also an interesting discussion of assassination that might easily have referred to suicide bombers in another time:

“Let it be noted that deaths like this, which are the result of a deliberate and fixed resolve, cannot be escaped by Princes, since anyone who disregards his own life can effect them. A Prince, however, needs the less to fear them as they are seldom attempted.”

Apparently, since Machiavelli turned out later in life to be a liberal forward-thinker, many have argued over the centuries since the publication of The Prince that it’s a satire and was never intended to be taken seriously. Again, I’m not sure if it’s the translation but I didn’t detect any irony at all.

I’m glad I’ve read it and I can see how you could write many more words analysing the text than the original contains, but I am in no great hurry to read more old political philosophy. Especially not if military strategy is a common theme.

First privately distributed in 1513 under the Latin title De Principatibus (About Principalities).

First published by Antonio Blado d’Asola in 1532 as Il Principe.

This translation first published by P F Collier and Son in 1910.

Source: I honestly don’t remember. It’s a US edition so maybe one of my holidays over that side of the pond?

Challenges: This counts towards the 2013 TBR Pile Challenge.