Everyone lives in the world they deserve

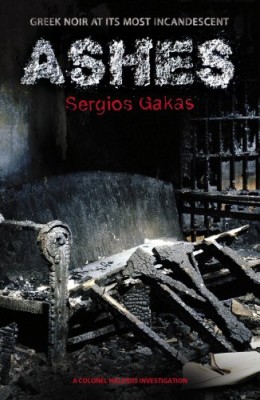

Ashes

by Sergios Gakas

translated from Greek by Anne-Marie Stanton-Ife

I took this book on holiday with me because crime is usually a good bet for an absorbing throwaway read. This book didn’t quite live up to that expectation, being both better than expected but also in some ways worse. I probably need to explain.

For a start this is one of the more literary police procedurals I have ever read, inasmuch as the writing is very good, a little experimental even, and it doesn’t follow the expected rules of the genre. Now that may partly be because it’s Greek, and perhaps they have their own set of rules. I’m not familiar enough with Greek literature to know. But this certainly didn’t read like it was slotting into a template.

“Let me break your seal, Stoli, my love. My red beauty, come here, give yourself to me, transparent like all my mistakes…I don’t feel good, damned wine, it’s all your fault. Armchair – prepare yourself. My sweet throne, I’m coming…Who’s that creeping around outside – who’s after my vodka? It burns, the bitch…It burns like hell: fight ice with ice, fire with fire…No! My face is burning, don’t, why won’t you listen to me? No, please.”

There are some familiar themes. The detective, Police Colonel Chronis Halkidis, is middle-aged, divorced, disillusioned, addicted to cigarettes (and some rather stronger illegal drugs to boot) and doesn’t follow the rules. So far, so familiar. I didn’t warm to Halkidis, especially as his addictions and methods became, well, worse. But that’s fine, I don’t need to like the main character.

“Three dark-haired types with shiny accordions were playing songs, a hybrid, it seemed, of children’s songs and revolutionary battle cries. The audience was singing along, miming the foreign lyrics with adolescent uncertainty. They were happy. I hated them. I ducked quickly into the toilet and snorted two fat lines of powder… Everyone lives in the world they deserve, and my particular world cannot take any more accordion music.”

The book opens with the crime and follows the police investigation, which again sounds traditional enough. The crime in question is the burning to the ground of a house in a suburb of Athens, a fire which takes hold so quickly that three of the house’s occupants are killed almost immediately and the fourth, a formerly famous actress called Sonia Varika, is left in intensive care with severe burns.

“‘Do you believe in God?’

‘No.’

‘Pity. If you did, I would recommend prayer. It would save me the more pedestrian option, where I explain to you that the human body is a machine, with a highly complex mechanism that we barely understand, but a machine nonetheless…Do forgive me if I come across as a vulgar materialist, but so far the only ones I’ve seen performing miracles and saving lives have been doctors and nurses. God has never once put in an appearance, not even to stitch up an eyebrow.'”

It took me a while to figure out the narrative voice, which alternately follows Halkidis and the landlord of the destroyed house, Simeon Piertzovanis, but there are also sections in italic, which are either memories or thoughts of Sonia from her coma. Almost the first thing we learn is that both Halkidis and Piertzovanis are former lovers of Sonia, which means that they both distrust one another but also form an uneasy alliance in their search for truth and justice.

Piertzovanis was an interesting character, a lawyer, gambler and alcoholic who has inherited enough money to not really need to work, he is somehow still largely likeable. And there was a good cast of secondary characters, from a girl Piertzovanis picked up the night of the fire and who has stuck around, to Halkidis’ small team of trusted police, to the various shady types involved to varying degrees in a crime that is somehow political, or at least large enough organisations are involved for solving it to get political.

“I dropped Piertzovanis off at the statue of Kolokotronis, waited for him to take a piss on it and then lurch across Stadiou, his arm raised to deflect the oncoming traffic; drivers were drowning him in hoots, obscene gestures and abuse, but they spared his life.”

So the people and their relationships kept me interested, plus the writing was good, so why didn’t this work for me? I think where it fell down was the crime/detective/thriller part. I’m not sure which of those three it was aiming to be because I didn’t think it worked as any of them. The solution to the crime was too convoluted, with no clues for the reader to follow. But I also never felt, for all of Halkidis’ antics, that he was ever in any danger, so it didn’t work as a thriller either.

Really, this is all about the detective not the detection. And the personal angle definitely added a certain something. Reading what I’ve written it sounds like I’m bothered because I can’t categorise the book and it surprises me that I should feel that way. Perhaps it’s even that the writing was lyrical enough that it slowed me down – I wanted to pay attention to the words, not fly through them. But whatever the reason, I wasn’t gripped, and that feels like a flaw.

First published in Greece by Kastaniotis Editions in 2007.

This translation published 2011 by MacLehose Press, an imprint of Quercus.

Source: This was a review copy passed on to me by fellow blogger Ellie of Curiosity Killed the Bookworm.

Challenges: This counts towards the 2013 Translation Challenge.