Dark suggestions of extramarital affairs, hidden wealth and poisoning

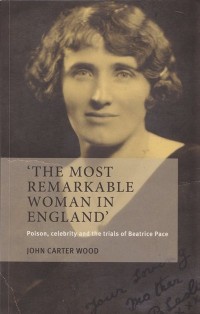

The Most Remarkable Woman in England:

Poison, celebrity and the trials of Beatrice Pace

by John Carter Wood

I think I first heard about this book in the Guardian, which goes to show that I do still occasionally read newspaper review pages and like something I see there. Now, I mostly liked the sound of this book because it’s about a historical event (okay, a death that may or may not have been murder) in the Forest of Dean, but it’s about so much more than that, tapping into issues around celebrity, poverty, gender equality, domestic violence and depression.

The history being recounted here is that of Harry Pace, a quarryman and sheep farmer who died in 1928 slowly and painfully, aged just 36, and his wife Beatrice Pace who was accused of murdering her husband by poisoning him. The long-drawn-out inquest and subsequent trial were the sensational news story of their day, not just locally in the Forest of Dean but also nationally, with details both revealed and (amazingly) kept hidden about infidelities, domestic violence and other dark secrets.

“[Harry Pace’s death might have] remained as obscure as that of any other working-class person. But investigations by the local police were soon accompanied by dark suggestions of extramarital affairs, hidden wealth and poisoning. The local coroner’s decision to postpone the funeral and order an urgent post-mortem suddenly made Harry’s demise newsworthy, especially when it was later proven that he had died from a large dose of arsenic. Precisely how it had gotten into his body was anything but clear, but there were only three obvious possibilities – accident, suicide or murder – and, at first, no way of deciding among them.”

You might think that a book about a mysterious death in (or very near to) my hometown back in the 1920s sounds a bit gruesome and/or specialised. But while the setting was certainly the reason for my initial interest, it was the way the story was told that kept me hooked.

Because this is a really well written book. Wood, a historian, acknowledges himself on his blog that he was trying to write for both a general audience and an academic one, and I think that shows, but not at all in a bad way. I have tried to read a few historical books written for a popular audience and generally I’ve struggled. Even the super successful The Suspicions of Mr Whicher, which it’s hard not to compare this to, didn’t entirely get it right in my view.

The way in which Wood does get it right is, to begin with, his identifying what it was about the case that made its players instantly famous. He has some very smart things to say about celebrity culture being tied to social and political changes, such as women’s liberation or distrust of the police force. Wood quotes extensively from original sources, which serves two purposes: you are left in no doubt as to where each fact/opinions comes from, and you get a real flavour of the time and place. Papers quoted Beatrice and other key witnesses extensively (and indeed both Beatrice and her oldest daughter had their stories serialised in the national press) so there’s lots of material to be drawn from and Wood has done an admirable job picking out the right lines to tell his story.

“The ‘seemingly interminable’ inquest stretched through April and May, attracting ever more attention. By mid-May, the World’s Pictorial News observed: ‘Throughout all these months of inquiries, throughout all the ten hearings before the Coroner, the widow has been called upon to face the gaze of curious eyes. Crowds flocked into Coleford from villages for miles around to see the woman who had become such a figure of public interest.'”

Because this is after all Wood’s story above all. He works at the Institute of European History in Germany, specialising in the history of crime, policing, violence and media; and those interests are very much at the fore. Which is in many ways what makes this book interesting – it doesn’t just lay out the facts and then have a stab at “solving the case”, instead it uses the case as a detailed case study. And they’re all fascinating subjects that are still relevant now.

I know that this book worked in a narrative sense because for most of the time I was reading it I felt a prickling at the back of my neck that I only get from a good crime book, whether true or fictional. It really is a very readable book, despite its extensive references. I’ll keep an eye out with interest for the next research interest Wood decides to expand into a whole book. I’d also like to thank Wood for e-mailing me with the genuinely interesting fact that the journalist most involved in covering the Pace case, Bernard O’Donnell, was the father of Peter O’Donnell, who created (and wrote the many many stories about) the character Modesty Blaise, who I really like. That’s a good fact.

Published 2012 by Manchester University Press.

Source: Christmas present from my Mum.