The time from the other room beats waves

The Passport

The Passport

by Herta Müller

translated from German by Martin Chalmers

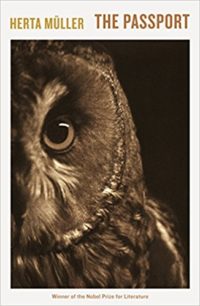

I bought this book in Berlin a couple of years ago, attracted by the cover line “Winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature”. And the owl on the cover, if I’m being honest. I had no idea what the book was about, when it was written or who Müller was.

Having read the book, I am surprised to discover that it’s set in Romania, not Germany, and it’s about events that happened in my lifetime, under a dictator I had heard of but did not know the full extent of his awfulness. (The Berlin connection is that Müller fled from Romania to Berlin and she has lived there since 1987.)

This is the story of a village in a minority German-speaking corner of Romania in the 1980s. Ceaușescu’s regime is increasingly oppressive, and this minority in particular are being killed – or to call it by its true name, ethnically cleansed. Most people in the village are trying to get out, and they will all do whatever it takes to get that precious passport. The main character, Windisch, a miller, is bribing the mayor with sacks of flour, but he knows what all the officials really want and he is trying to resist. He talks unkindly of how his fellow villagers managed to obtain their passports, but it is inevitable that he will have to follow in their footsteps.

“Every day when Windisch is jolted by the pot hole, he thinks, ‘The end is here.’ Since Windisch made the decision to emigrate, he sees the end everywhere in the village. And time standing still for those who want to stay. And Windisch sees that the night watchman will stay beyond the end.”

Müller obscures some of the darkest facts of life with dream-like images; I suppose the implication is that the characters are living through a nightmare, so why not use the language of nightmares: ominous animals, rising waters and objects changing shape. The juxtaposition of stark reality and surreal, dark-fairytale-like moments may have made the bleak story easier to swallow, but it was still upsetting.

Windisch’s daughter Amalie lives in town, working as a teacher. In a chilling section she recites to her class the party line about Nicolae and Elena Ceaușescu being the father and mother of the nation and how all children love them. A few pages later Windisch’s wife is breaking the news to him that party officials came while he was at work and took away most of their hens and eggs, extracting a promise for most of their crops and telling them what to plant next year.

In this atmosphere, who can be trusted? Those who have the tiniest power must choose whether to take advantage. The postwoman might choose to pocket the money she is given and not post important paperwork. The night watchman might choose to turn a blind eye when he sees a man dropping off a sack at the mayor’s door that has not been recorded in any business’s records. The priest might choose to make a ritual of finding your birth certificate – a ritual behind closed doors that everyone knows about but only speaks of in elliptical allusion.

“Rudi holds a spoon of blue glass to his eye. The white of his eye grows large. His pupil is a wet, glistening sphere in the spoon. The floor washes colours to the edge of the room. The time from the other room beats waves. The black spots float along. The light bulb flickers. The light is torn. The two windows swim into one another. The two floors push the walls in front of them. Windisch holds his head in his hand. His pulse is beating in his head. His temple beats in his wrist. The floors lift themselves. They come closer, touch. They sink down into the crack. They will be heavy, and the earth will break.”

When your life is under threat and you can’t trust your neighbours, it’s no surprise that Windisch is often in a bad mood. He talks cruelly to his wife about what she did to survive the war. But he must know, as we learn from a flashback, that it truly was a matter of survival. More immediate and obvious even than their situation is now – what are they all willing to do this time?

Müller’s prose is powerful and I was curious whether, having won the 2009 Nobel prize, other works of hers have been translated. It looks like Portobello Books has taken the lead, but a few other publishers have shown interest. I’m glad, as this is definitely a voice that should be heard.

Der Mensch ist ein grosser Fasan auf der Wels published 1986 by Rotbuch Verlag.

This translation published 1989 by Serpent’s Tail.

Source: Kohlhaas & Co, Berlin.