Wherever I go on the island, you’re with me

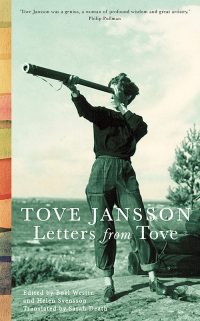

Letters from Tove

Letters from Tove

by Tove Jansson

edited by Boel Westin and Helen Svensson

translated from Swedish by Sarah Death

This is a giant warm cuddle of a book. It took me a while to read as the letters are many and to some extent a little repetitive, but I loved effectively being able to hear Tove Jansson speak honestly to the people she was close to. The book only includes Tove’s letters, not the other half, so there is always part of the conversation missing, which also makes it a little bit of a mystery puzzle.

The correspondence is organised by addressee, beginning with letters that Tove sent to her family when she went to art school in Stockholm, and then two long trips to France and Italy to further her art education. Young Tove was very adventurous, sociable and passionate – about art and about people. I laughed out loud at her descriptions of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where she was treated awfully and quickly left for a smaller school where she felt she was actually learning.

Her parents were both artists themselves and lived for part of every year in an artists’ colony – a lifestyle that Tove carried into her own adulthood, but it often clashed with her desire for solitude and peace, and this clash is something that is increasingly the focus of her letters. But her biggest fight is always with her own art.

“This profession is sheer agony sometimes. You know, days when you just wander around, nothing gives you the urge to paint it, nothing comes to life…every failed blotch of colour makes you feel tired to death – in the small of your back…Sometimes something emerges. And then you’re overtaken by this anxious fervour…If a picture suddenly gets that ‘something’, a promise, an intensity – you can stand at the easel furiously redoing canvas after canvas. Then the empty days return, nothing but a waste of paint.”

– Letter to Eva Konikoff, 14.5.46, Helsinki

Another major topic is her love life. Tove had many lovers, male and female, and writes freely about her affairs, about falling in love, about moving on from break-ups. Three of her romantic partners are given sections in this book. The first is Atos Wirtenen, a Swedish politician who dated Tove from 1943 to the early 1950s. They never lived together but discussed marriage and other long-term plans. Tove clearly shows affection for Atos in her letters to him and about him, but she doesn’t display passion for him. That contrasts with her letters to and about Vivica Bandler, a theatre director and Tove’s first female lover, with whom she had a relationship in 1946 that was only brief but had long-lasting effects. Vivica remained a close friend of Tove’s, which was not always an easy balancing act with their future partners.

Tove’s longest-lasting relationship was with fellow artist Tuulikki Pietilä, from 1956 until Tove’s death in 2001. Though they lived together fairly quickly, they rarely spent the whole year together. Tove usually spent all or part of her summer with her family, and Tuulikki found it difficult to work in that environment, which caused friction for the couple. This gave them lots of letter-writing opportunities and their love is clear and evident. They generally wintered in Helsinki where they had adjoining studios.

“The Island looked very solemn without you when I arrived here at sunset. It had turned in on itself and I felt like a virtual stranger. It was only when I got up to the house that it looked friendly and alive again. The wagtails were yelling in great agitation, complaining volubly because the copper jug we had our midsummer leaves in had fallen down and clearly scared the babies out of their wits…Now the idyll has been restored and the mother is so tame she stays perched on top of the flagpole…Wherever I go on the island, you’re with me as my security and stimulation…And if I left here, you would go with me. You see, I love you as if bewitched, yet at the same time with profound calm.”

– Letter to Tuulikki Pietilä, 26.6.56, Breskär

As Tove gets older, she writes more about nature and particularly the islands in the Gulf of Finland where she spent the summer. There was a major storm in August 1967 that she describes in at least three letters, but it’s Tuulikki who gets the full detail of Tove and her brother Lars trying to save all the boats without risking their lives. It’s fantastically dramatic but also includes comical details such as how many sets of clothes were soaked through.

Of course, Tove talks to all her addressees about her work. Over her lifetime she produced paintings, plays, songs, comics, murals, novels and short stories. She collaborated with Lars on the Moomins when they became hugely popular and he helped her with the comic strips and TV shows, eventually taking over both from Tove. She turned more towards writing fiction and seemed prouder of those efforts than she ever was of the Moomins, whose success sometimes seems to have been a source of frustration and bemusement for her (though she did concede that the money was nice to have).

But the Moomins are in many ways a reflection of who Tove was, with their emphasis on family extending beyond blood relations, their descriptions of nature, and living simple lives, their acceptance of other people who are different in various ways. And Tove used the language of the Moomins in her letters for years, as well as including lots of Moomin cartoons. Many of the Moomin characters are based on people she was close to, such as Too-ticki being Tuulikki. The characters Tofslan and Vifslan (renamed in the English translations as Thingumy and Bob) are coded versions of herself and Vivica, and in her letters to Vivica she often used these names.

To an extent Tove had to learn to use coded language because it was illegal to be in a gay relationship in Finland until 1971. She uses the euphemisms “ghosts” and “phantoms” to refer to her gay friends (or gay nightclubs when she travels) and this sticks even later in life. She asks several of her correspondents to burn her letters (which they clearly either didn’t do at all, or didn’t do completely). Later in life she openly took Tuulikki as her partner to events such as award ceremonies, and they even wrote a book together about their island home, but for much of Tove’s life her mother was her official plus-one. There are very few letters in which she addresses her sexuality directly, but that’s understandable given the timing. The book’s editors – who helpfully provide an introduction to each addressee and notes on each letter – mention that Tove’s best friend in her early life, Eva Konikoff, disapproved of Tove’s self-described decision “to go over to the ghost side” in the early 1950s but there is no indication that anyone else in her life had a problem with it.

The letters to Eva, who moved to America in 1941, are the most interesting from a historical perspective as the majority were written during and shortly after the Second World War. Tove describes many an air raid and scene of destruction, as well as the difficulties of rationing, the fear of male friends and relatives going off to fight, and of course the lives lost. One detail from Tove’s wartime letters that I enjoyed was her notes to the censor. Several include under the date a line like “Censor: written in Swedish” or even in one case “Censor, please don’t delete anything, it’s only me! Tove”.

“The great events unfolding around us, rather than widening our horizons, have shrunk them into petty stubbornness, we get manically hooked on the phraseology of misdirected nationalism, on slogans…The whole world is in chaos. A world where all that we thought best, found just and sound, is no longer venerated and so much that we repudiated has been raised to become the rule of law. Of course, we try to cling on to what we believe in…But what’s hard is…to quell every tendency to bitterness, which it would sometimes almost be a cowardly relief to burrow down into.”

– Letter to Eva Konikoff, 3.12.41, Helsinki

After that period, there is a timelessness to Tove’s letters, because she almost never mentions politics or historic events, rather concentrating on art, the people she loves and the places she loves. Politics is in some ways an odd omission considering that her earliest published work was satirical cartoons in the anti-Fascist magazine Garm – including the first versions of the Moomins. But it’s another topic that Tove probably had to learn to be careful about in written communication. Atos Wirtenen was “part of the radical left and forced to go underground on several occasions”, according to the book’s editors. She refers to delivering “a secret document” to him and may well have hidden him on one or more occasion. Tove also refers to arguments with her father about politics.

The final topic covered, perhaps inevitably, is ageing. There are fewer letters from Tove’s later life, but those there are show a combination of sorrow and relief at getting older. There is a tumultuousness to young Tove that seems to subside into contentment, but she still refers occasionally to melancholy and even depression. Perhaps it is unavoidable that an intelligent, passionate person will feel extremes of other emotions too, but on this topic as with everything else, Tove is articulate and open.

I loved this book, and I am relieved that seeing this personal side of Tove Jansson has only deepened my admiration for her. She was a great letter-writer, with an eye for those small details in life that amuse or add colour, and of course a penchant for philosophising wisely.

Brev från Tove Jansson first published 2014 by Schildts & Söderströms.

This translation published October 2019 by Sort Of Books.

Source: A copy was kindly sent to me by the publisher in return for an honest review.