I accepted loneliness as a way of life

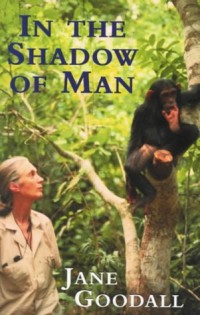

In the Shadow of Man

by Jane Goodall

While famous in the world of science, Goodall is perhaps lesser known to the rest of the world than her American counterpart Dian Fossey thanks to Hollywood and Sigourney Weaver, but Goodall is apparently the better writer. I certainly enjoyed this example of her writing, with a few reservations.

This is the second of Goodall’s 26 books to date, most of which are about the chimpanzee study that occupied her for more than 40 years. As such, it’s very much the beginning of her story and I’m aware, both from the 1988 foreword added to this book and further details online that much has changed since, both in Goodall’s life and in our knowledge of chimpanzees, and therefore my review is at a disadvantage by being based only on the book I have just read.

Goodall knew as a young woman that she wanted to study animals, so she worked hard as a waitress to raise the money when an opportunity arose for her to visit Kenya. In Africa she got herself a job so that she could stay until she had wrangled herself an invite to meet the great naturalist Louis Leakey. He saw her passion and gave her the job of studying chimpanzees at Gombe Stream in Tanzania. He told her from the start it was a solitary and long-term project – a previous study of two months had been woefully inadequate – and Goodall gamely rose to the challenge.

“I accepted loneliness as a way of life…I became immensely aware of trees; just to feel the roughness of a gnarled trunk or the cold smoothness of a young bark with my hand filled me with a strange knowledge of the roots under the ground and the pulsing sap within…I loved to sit in a forest when it was raining, and to hear the pattering of the drops on the leaves and feel utterly enclosed in a dim twilight world of greens and browns and dampness.”

This is a memoir as well as a scientific book, but most of all it is the story of the specific group of chimps that Goodall got to know over many years (this book covers the first decade). You can watch her early progress as a scientist, as the first part of the book describes her gradually learning to do the job through trial and error, while the latter half is effectively her actual study results. These chapters are split fairly scientifically into subjects such as hierarchy, feeding, parenthood and death, but Goodall always uses specific examples to illustrate her general observations. She is a storyteller and she has a fascinating, sometimes moving story to tell. I even shed tears at one point.

The book is a little dated, in multiple ways. Goodall’s tone is often preachy when it comes to human behaviour, sometimes to a cringeworthy degree. Though tied into this are the clear beginnings of her activism in animal protection, which obviously I am wholeheartedly behind. The fact that she so often compares human behaviour with that of the chimps feels old-fashioned and unnecessary (but admittedly, that is the entire basis of the book’s title). But most of all the scientific study itself feels dated. Then again, even within the first 10 years Goodall learned from her early mistakes – for instance, their initially high level of artificial feeding of the chimps was heavily cut back over time.

“Would Mike have become the top-ranking male if my kerosene cans and I had not invaded the Gombe Stream? We shall never know, but I suspect he would have in the end. Mike has a strong ‘desire’ for dominance, a characteristic very marked in some individuals and almost entirely lacking in others.”

I know that some people have accused Goodall of anthropomorphism because she named the chimps (and some of the local baboon population) that she studied, but I disagree with that criticism. Naming an animal is not the same as describing it in human terms, and the latter is something that Goodall never does; in fact, she is careful to specify that is not what she means when she describes something that could be construed as close to a human response. She was the first to observe many key aspects of chimp behaviour, including tool-making and meat-eating. I really felt I learned a lot about chimpanzees from this book and would be interested to find out how much more we know now, after more than 50 years of close study, in Tanzania and, later, elsewhere. (The Gombe Stream base started taking on students quite early on in Goodall’s career and is still going now.)

“I cannot conceive of chimpanzees developing emotions, one for the other, comparable in any way to the tenderness, the protectiveness, tolerance and spiritual exhilaration that are the hallmarks of human love in its deepest sense. Chimpanzees usually show a lack of consideration…which in some ways may represent the deepest gulf between them and us.”

For all its 1970s moralising, this book is never prudish about the facts of life. Goodall describes simply and factually everything about the chimps, including their sex lives, their toilet habits and how they deal with death. She maintains the same matter-of-fact tone about her own life, which is slightly disconcerting when she is telling the story of her romance with and marriage to Hugo van Lawick, a National Geographic photographer who was selected to go to Gombe Stream by Louis Leakey, who had a hunch that Hugo and Jane would hit it off. Hugo managed to get his assignment in Tanzania extended and started helping out with the chimp study so that soon he and Jane were working closely together, which they continued to do throughout their marriage. There are many of Hugo’s photos in the book, a nice touch that helps bring the story to life.

I think now I really should read books by Louis Leakey’s other famous protégées, Dian Fossey and Biruté Galdikas, though I might need to take a break in-between so I don’t overload on great apes!

Published 1971 by Houghton Mifflin/Collins.

Source: Borrowed from a friend.

Challenges: This counts toward the 2014 Popular-Science Reading Challenge.