The extraordinary silence of these long, self-contained days

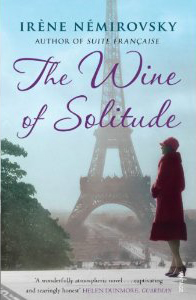

The Wine of Solitude

by Irène Némirovsky

translated from French by Sandra Smith

Since reading Suite Française when it was discovered and released I have been eager to read more of Némirovsky’s early novels. This is my second and so far they have failed to come close to the brilliance of her final, inspirational work. Not that this is by any means a bad book, but I suppose I had been expecting something more.

I suspect some of Némirovsky’s own life fed into this novel. It follows a family with a Jewish father who move from Ukraine to Russia to Finland to Paris in the 1910s and 1920s, so the background is the First World War, the Russian Revolution and the stock market rise and fall. Which is a turbulent, exciting and occasionally terrifying background for what is at heart the coming of age of a young woman.

“The smell of cigars and brandy wafted through the house until morning, slipping beneath her door and insinuating itself into her dreams. A faraway rumbling shook the paving stones: artillery detachments were passing by in the street.”

But it’s not that simple. Hélène dearly loves her father but he has no time for her between his gambling and business affairs – everything is about making money for Boris Karol. And Hélène’s mother should never really have become a mother at all, as she just wants to party, have affairs with young men and buy expensive clothes and jewels. Hélène harbours quite deep hatred of her mother, which becomes more bitter as she gets older.

“When she was ten years old she began to find a melancholy charm in the solitude of these Sundays. She liked the extraordinary silence of these long, self-contained days, which were like faint little suns in a different universe where time flowed at a slower pace.”

There is a lot of negative emotion in this book, as if Némirovsky is pressing home the point that money does not equal happiness. In fact, the brief interludes of happiness for Hélène are determinedly simple pleasures – going for afternoon walks with her French governess, sledging in snow, childhood summers in Paris playing with children who don’t judge her for being different, for having fashionable clothes and speaking better French than Russian. But mostly her early life is unhappy. Not terrible or desperate, but unhappy. And part of her journey to adulthood is learning to find and enjoy those simple pleasures, and making the decision whether to be cold and strong like her mother or passionate but breakable like her father.

“A storm was brewing over Paris; the sky was covered in copper-coloured wisps of cloud that slowly moved closer together to form a blanket of pink mist that parted every so often to reveal a dazzling ray of light.”

There is some beautiful writing here, especially in the descriptions of places, but I found the dialogue and descriptions of emotions a little simplistic or false-sounding. There would be pages of Hélène analysing herself in a manner both too detached and knowing but also naively that for me broke the spell.

“No, I won’t read. All those books make me anxious and unhappy. I have to be happy; I have to like other people…Tonight, I’ll cut out pictures, I’ll draw—I’m happy; I want to be a happy little girl.”

Not that it wasn’t worth reading. And I certainly think there is more to this book than the cover art lets on (a terrible cliché of the elegant young woman in Paris, which doesn’t come close to expressing the darkness that this book contains). It just suffers from my having read what was probably Némirovsky’s best before I read the rest.

First published as Le vin de solitude by Editions Albin Michel in 1935.

This translation published 2011 by Chatto & Windus.

Source: This was a present from my Dad for Christmas 2012.

I must admit I was most taken by the Appendixes and Preface of Suite Française. The true story outweighed the novel for me though it was compelling as well. I hear it is being made into a movie and is filming this year …. hmm. I didn’t realize or had forgotten that she had written other novels as well. Interesting to know. cheers. http://www.thecuecard.com/

Susan Yes, she was a fairly successful writer while alive but quickly forgotten on her death. Interesting about the film of Suite Francaise. Not sure it will work but I guess after Les Mis it’s an inevitable next step.