I want to go on living even after my death

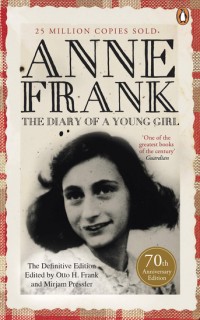

The Diary of a Young Girl

by Anne Frank

edited by Otto H Frank and Mirjam Pressler

translated by Susan Massotty

This Definitive Edition of the diary of Anne Frank is not, according to the publisher’s note, intended to replace the earlier version edited by Anne’s father Otto shortly after her death, but instead to serve as a more accurate historical record for those who have already read the (quite heavily) edited version. It is in some ways quite a different book and almost makes me want to refer to the Critical Edition, which compares Anne’s original diary, her own edits and her father’s edits.

This is one of the aspects of the diary that I only learned this year – Anne Frank edited and rewrote the majority of her own diary in early 1944 after hearing on the radio that the Dutch government wanted after the war to collect eyewitness accounts of Dutch people who had lived through the German occupation. Otto Frank’s edit combined material from both versions of Anne’s diary and even some accounts she wrote about life in hiding that had been thinly veiled as short stories. The Definitive Edition is almost entirely composed of Anne’s self-edits, which I like because that is what she intended to have published herself – it’s why she went to the effort of doing all that editing.

“I don’t want to have lived in vain like most people. I want to be useful or bring enjoyment to all people, even those I’ve never met. I want to go on living even after my death…When I write I can shake off all my cares. My sorrow disappears, my spirits are revived!”

The Definitive Edition is quite a bit longer (30% apparently) than Otto Frank’s edit, because he cut a lot of stuff out. Partly this was because the original publisher was aiming at a young adult audience and therefore wanted something short and without any references to sex or puberty. And Anne, pardon the pun, could be very frank with her diary, which she called Kitty and spoke to like a friend (she even, in some places, writes as though she is addressing questions that Kitty has asked her). But the thing that struck me most reading this edition is that most of what had been cut out was material that might be considered unflattering or even outright cruel about the other occupants of the annexe, especially her mother.

I should probably include a summary of Anne Frank’s story for those who don’t already know it. Otto Frank was a successful businessman in Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany, which is where Anne and her older sister Margot were born. In 1933, when Anne was four, changes to German law regarding Jews led to the family moving to Amsterdam, where Otto continued his business, Opekta. In 1940 the Netherlands was occupied by the Nazis, who immediately introduced anti-Jewish laws there. Otto and his business partner Hermann van Pels signed their business over to a trusted non-Jewish colleague and the girls had to move to a Jewish school, but Otto and his wife Edith anticipated worse to come and soon began planning a safe hiding place. In 1942 a summons arrived for Margot and within days the Frank family was installed in the Secret Annexe – a building attached to the back of the Opekta warehouse that had formerly served as a laboratory and extra office space. The Van Pels family joined them there (Anne gave them pseudonyms in her edited diary, so you may know them as the Van Daans), as did family friend Fritz Pfeffer (Albert Dussel in the diary). They remained hidden for two years, until 4 August 1944, when the SS arrested all eight occupants of the annexe. They were taken to various concentration camps and only Otto Frank survived the war. When he returned to Amsterdam, one of the Opekta secretaries who had helped the families to hide gave him Anne’s diary, which she had retrieved from the annexe and hidden.

“[Miep] brings five library books with her every Saturday, We long for Saturdays because that means books. We’re like little children with a present. Ordinary people don’t know how much books can mean to someone who’s cooped up.”

The diary really is a mixture of many things. It’s an open, honest account of being a teenager, and the joys, frustrations, changes and experiences that most girls will have between 13 and 15 years old (the diary was given to Anne on her 13th birthday, in June 1942). It’s also a record of someone learning to be a writer, from before she harboured that ambition, through discovering it, to beginning to refine her work and identify what kind of writer she might be. It is of course a historical record of being a Jew under Nazi occupation, of Amsterdam in wartime, with all the food shortages and the thefts and suspicion that follow on from privation. And it’s a study of people under intense pressure, squeezed into a fairly small space physically but of course it’s the psychological pressure that made it really claustrophobic.

“I’ve been taking valerian every day to fight the anxiety and depression, but it doesn’t stop me from being even more miserable the next day. A good hearty laugh would help more than ten valerian drops, but we’ve almost forgotten how to laugh. Sometimes I’m afraid my face is going to sag with all this sorrow and that my mouth will permanently droop at the corners.”

Having been to the building itself, at 263 Prinsengracht, Amsterdam, helped me to visualise a lot more of the diary this time around. The annexe was in effect insulated from the warehouse (where none of the workers knew anyone was hiding upstairs) by the Opekta offices, where all the regular staff knew about the occupants of the annexe and helped them a great deal. The neighbouring buildings were all businesses, and therefore empty at night. But although this allowed them to make at least a little noise, they still had to be extremely careful not to ever be seen, so blinds or curtains were kept drawn and windows could only be opened a little overnight, but had to be strictly closed during the day. Outside of business hours they did sometimes leave the annexe and use the rest of the building – most of them took their baths in the office or the office kitchen and they sometimes used the office kitchen to cook – but as break-ins became more frequent this became ever more dangerous.

“I see the eight of us in the Annexe as if we were a patch of blue sky surrounded by menacing black clouds. The perfectly round spot on which we’re standing is still safe, but the clouds are moving in on us, and the ring between us and the approaching danger is being pulled tighter and tighter.”

I don’t remember from my previous reading of the diary there having been so many break-ins and other near-misses and I found myself, in the last couple of months of the diary, thinking each time – was that it? Was that time they forgot to unbolt the warehouse door, or that time the warehouse manager spotted an open window, or that time they actually chased off burglars from the warehouse, the time that someone realised people were hiding there and reported it? It’s genuinely chilling to read Anne describe them as near-misses when maybe one of them wasn’t a miss at all. (Though it could just as easily have been more mundane. A lot of people knew they were there, from food suppliers to official Jewish organisations, and a slip of the tongue or a beating from the police could have betrayed them.)

I realise I’ve written a lot without really reviewing the book itself. Partly that’s because it’s impossible for me to separate the book from the wider story that it’s part of. But of course I do have responses specific to the book. Despite Anne’s edits it is still brutally honest because that is who she was. She records her joys, her rages, her depressions, her contemplations and above all she judges herself. Often she will make a proclamation that sounds ill-thought-through and childish (that she is too independent to need her parents, for example), only to tear it down a few days later, berating herself harshly, especially when she has upset her father, who she doted on. But then there are also passages that are beautiful and/or insightful. She says a few times that she has had to grow up too fast, that going into hiding effectively stole her childhood, and of course she’s right. At 15 she is better read and much more politically aware than I was at that age, but it’s more than that. She becomes quite astute when it comes to understanding people and their motives. Where in 1942 she simply dislikes most of the annexe occupants (her father and Margot are really the only exceptions, and even they come in for criticism), over time she learns to understand them all and be on better terms with them, though the relationships all remain volatile.

For the first half of this reread I didn’t think I had fallen for Anne the way I had previously. The extra material criticising her mother and Mrs van Pels/van Daan turned me off a little. But of course I was won over and if anything the change in Anne over time was more apparent and the ending more poignant. This wasn’t just yet another girl who dreamed of being a writer, this was someone capable of great things who sadly (that word is so inadequate) was only able to give the world one great thing, but what a gift it was.

Het Achterhuis first published 1947.

This translation first published by Doubleday in 1995.

Revised with extra material in 2001.

Yes I agree. Anne was capable of great, great things, If she had lived, she would have been a terrific writer of various notable books, I think. Lovely write up & review. You brought the Diary all back to me. Every decade I should reread it. Perhaps everyone should. Check out that Miep Gies book too! Gosh the ending to these books kills me though. No book is sadder

Susan I had a look at Miep Gies’ website. Sounds like she was a remarkable woman.