A dam-burst of ideas, memories, impulses and thoughts

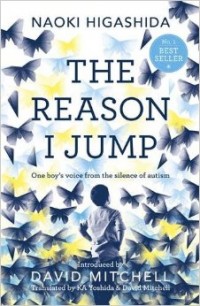

The Reason I Jump: One boy’s voice from the silence of autism

The Reason I Jump: One boy’s voice from the silence of autism

by Naoki Higashida

translated from Japanese by K A Yoshida and David Mitchell

This was one of those random finds that make a great bookshop great. Not that it’s the best book ever, but it’s genuinely interesting and different and, despite being fairly new and translated by one of my favourite authors (plus his wife), I hadn’t heard of it. But it was on display in the non-fiction shelves and Mitchell’s name jumped out at me.

This is somewhere between a memoir and a factual study of autism. Higashida is autistic and at the time of writing was just 13 years old. He struggled with vocal communication, behaviour problems and even written communication, but had worked with his mother and a teacher to create an alphabet-grid system whereby he pointed at words or letters to be understood. (He did also learn to type on a computer and started a blog, so this book isn’t entirely miraculous.) With this book he found a way to explain his experience of autism that was fresh and new to parents and other adults who have regular contact with autistic children. It’s written in the form of questions and answers, with a few very short stories dropped in. There’s some lovely sections about how important nature is to Higashida, partly because it places no demands on him.

“Why do people with autism often cup their ears? Is it when there’s a lot of noise?

…The problem here is that you don’t understand how these noises affect us. It’s not quite that the noises grate on our nerves. It’s more to do with a fear that if we keep listening, we’ll lose all sense of where we are. At times like these, it feels as if the ground is shaking and the landscape around us starts coming to get us, and it’s absolutely terrifying. So cupping our ears is a measure we take to protect ourselves, and get back our grip on where we are.”

For many readers, Higashida’s words were a true breakthrough in their understanding of their own autistic child, and the book was a minor hit in his native Japan. One of those readers was Yoshida, and she immediately started to translate the book so that she could share it, initially with her husband and friends in Ireland, and then, once Mitchell had done some polishing and written an introduction, they published it to reach a much wider audience. There has apparently been some controversy about how much Mitchell polished, with some readers saying this doesn’t sound like a child’s writing. I must say I wholly disagree. Higashida sounds if anything surprisingly typical for his age – presumptive, repetitive and a little self-obsessed, thinking he’s learned to see the wider world but not really anywhere close to that yet.

I don’t mean to sound unkind. This is a very interesting and readable book about a condition that is incredibly difficult to understand. While nothing Higashida has to say was totally revelatory for me and he presumes to speak for all children with autism as if his own experience is universal, I’m really glad I have read it and can definitely see how valuable it could be to anyone who deals with autism. But let’s face it, Mitchell’s introduction is the best bit.

“Imagine a daily life in which your faculty of speech is taken away. Explaining you’re hungry or tired is now as beyond your powers as a chat with a friend… Now imagine that after you lose your ability to communicate, the editor-in-residence who orders your thoughts walks out without notice. The chances are that you never knew this mind-editor existed but, now that he or she has gone, you realize too late how they allowed your mind to function for all these years. A dam-burst of ideas, memories, impulses and thoughts is cascading over you, unstoppably.”

First published in Japanese in 2007.

This translation published 2013 by Sceptre.

Source: The Melton Bookshop.