Leaving behind me a thousand little phantoms in my image

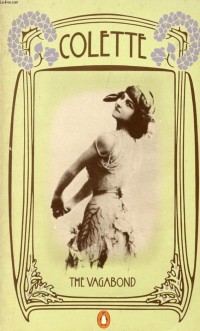

The Vagabond

The Vagabond

by Colette

translated from French by Enid McLeod

I love Colette. This slim, seemingly simple novel is beautifully told and explores in great detail the psychological weight of the decisions we make.

Renée is a music-hall dancer in Paris. Divorced and in her 30s, she has to perform in seedy venues late at night to pay her rent but she doesn’t mind that. In fact, she quite enjoys it, though it does give her a great fear of getting old, knowing as she does that it is her looks and not her talent that the crowds are attracted to. For now she has an agent who keeps her in work and a regular partner called Brague, a mime who designs and choreographs their act.

“Behold me then, just as I am! This evening I shall not be able to escape the meeting in the long mirror, the soliloquy which I have a hundred times avoided, accepted, fled from, taken up again, and broken off…Behold me then, just as I am! Alone, alone, and for the rest of my life, no doubt. Already alone; it’s early for that.”

It gradually becomes clear that Renée’s ex-husband was a wrong’un, a philanderer and emotional manipulator, and her independence was hard-won. So when a possible new love comes along, it brings real terror to Renée. But it’s not just the man himself and his potential power over her that she fears. It’s also the assumption among all her friends that she will give up her performing career, be content to rely on a man for everything again.

Is this pride, survival instinct, fear of what may go wrong or common sense? At the start of the novel, a fellow performer, the very young and initially naïve Jadin, disappears with a man to be his mistress. It seems to her colleagues left behind that this was both inevitable and a great shame. Are they jealous or do they know from experience what Jadin does not? Or is she smarter than they all realise, and simply making the most of every moment?

As always, Colette’s language is poetic but simple. She gorgeously evokes dressing rooms, parks, forests, train carriages and Renée’s tiny flat. She accurately prises open the hidden thought process behind Renée’s conversations with her friends, reflecting what she does and does not reveal, what she hopes to hear and what she fears will be said.

“A gipsy henceforth I am…A vagabond, maybe, but one who is resigned to revolving on the same spot like my companions and brethren. It is true that departures sadden and exhilarate me, and whatever I pass through…something of myself catches on it and clings so passionately that I feel as though I were leaving behind me a thousand little phantoms in my image, rocked on the waves, cradled in the leaves, scattered among the clouds.”

It’s perhaps a sign of the times that my tattered 1980 copy of this novel describes in the blurb the “chilling climax”, which I did not find chilling at all and I don’t believe that Colette intended it to be. I don’t know if that’s an attempt to make the book sound more melodramatic than it is by far, or if the blurb-writer genuinely considers Renée’s story to have a disturbing ending, but to a modern reader it’s unlikely to shock or disturb. (And frankly I’m surprised that it could have in 1980, which was almost 70 years after the book’s first publication, when I can well see that the story as a whole might have been shocking.) This is a quiet, subtle book, realistic and nuanced.

It being realistic of course makes sense considering Colette’s own life at this time. Like Renée she was divorced from a man who had taken advantage of her writing ability and claimed her works as his own. Like Renée she turned to performing in music halls in Paris. One reason that Renée’s friends give her for considering accepting the relationship with a new man is that it will give her time to write again. That is the choice Colette herself made, remarrying in 1912 and devoting herself to writing, but she had already written The Vagabond by then. Did she give her character the same choice to work through the decision before her?

“There reappears before me, with his childish rage, his bestial persistence, his calculated sincerity, my enemy and my tormentor: love. There is no mistaking it. I have already seen that forehead, those eyes, and those hands convulsively gripping each other, yes, I have seen all that…But what am I going to do? How shall I answer him? This continuing silence becomes more embarrassing than his avowal. If only he would go away.”

Colette’s life was eclectic and fascinating, and in semi-autobiographical novels like this we get a glimpse of it that I find tantalising. She did also publish memoirs much later on, which I’d love to read, but there is something to be said of the immediacy of her writing, with just a thin disguise, about the life she was living right there and then. Did she really sleep on the same bed that had been her marriage bed and feel a complex combination of revulsion and affectionate nostalgia for it? Did she really feel, in her mid-to-late 30s, that she was ruined for all future loves? I suspect the answer in her memoirs, 30 years later, would be rather different.

La Vagabonde first published 1911 by P Ollendorf.

English translation published 1954 by Martin Secker & Warburg.

Source: This was clearly secondhand but I don’t remember where from. My guess would be either the Oxfam Bookshop on Park Street, Bristol, or Beware of the Leopard.

Challenges: This counts toward the Classics Club.