The unreliable measuring device of words

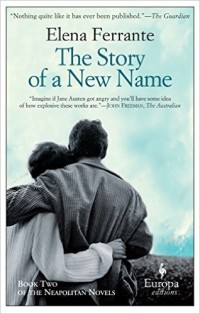

The Story of a New Name

The Story of a New Name

by Elena Ferrante

translated from Italian by Ann Goldstein

This is book two of the famed Neapolitan Novels, which started with My Brilliant Friend. This review does contain spoilers for the first book, which I also highly recommend. Arguably you could come to this book cold – everything you need to know from book one is repeated – but you’d be missing out on a key part of the experience in my opinion.

Elena and Lila are on the verge of adulthood. Married at 16, Lila is gradually realising that marriage is not a quick fix to make her brother rich, and that being married to someone she doesn’t love is fine until she does fall in love.

For Lila, marrying Stefano, the grocer, was supposed to be the lesser of two evils – her other rich suitor in book one being Marcello Solara – but either way Lila is tied up with the dangerous Solara family and not in the powerful position as one of their wives. Did she make the right choice? She spends frivolously and flirts with both Solara brothers despite her husband’s violent temper. Has she shut down all true feeling? She is smart and aware, surely she knows the dangerous ground she is treading?

“She was beautiful and she dressed like the pictures in the women’s magazines that she bought in great numbers. But the condition of wife had enclosed her in a sort of glass container, like a sailboat sailing with sails unfurled in an inaccessible place, without the sea.”

Elena is at first jealous of Lila’s riches, her freedom, her discovery of sex, her ability to run a business. But at intervals she is reminded that Lila’s lack of education, her marriage, tie her to this small impoverished corner of Naples, while Elena’s continuing education widens her world year after year.

As in book one, it seems that one girl or the other is always up while the other is down, and it is only towards the end of the novel, when they are in their early 20s, that they finally realise that their dreams are no longer the same, that they are not competing for the same prize anymore.

“Something passed rapidly between the two girls, their secret feelings darted infinitesimal particles shot at each other from the depths of themselves, a jolt and a trembling that lasted a long second; I caught it, bewildered, but couldn’t understand, while they did, they understood, in something they recognized each other.”

Except…are they in love with the same man? Elena vacillates, uncertain of her feelings, much like everything else in her world. She is never confident, never sure. She calls herself time and again a “brilliant student” (a callback to the title of book one, My Brilliant Friend?) but is this the narrator, Elena aged 66, using that label? Or is newly adult Elena at once aware of her brilliance and uncertain of how to use it?

She tells us that when she speaks about politics or social issues she merely parrots things she has read – and she has read widely and has a concept of what it all means, but she feels that she is not bringing her own thoughts to bear in the way that Lila always does. A case of impostor syndrome? A lack of awareness that everyone else is pretending to some extent too? Or is she only being realistic about her own limitations, about her need to find a different path in life than the one she has been hoping for?

“Movies, novels, art? How quickly people changed, with their interests, their feelings. Well-made phrases replaced by well-made phrases, time is a flow of words coherent only in appearance, the one who piles up the most is the one who wins. I felt stupid, I had neglected the things I liked to conform.”

Some serious issues are dealt with here – sex and all that it brings being a major theme – but the biggest thing, for me, was the position of women. Elena and Lila were raised to get married and be good wives. When they work it will be to their husbands’ approval and often part of the complicated politics between shop owners and moneylenders. Both girls defy expectations, in different ways. Lila marries too young – 18 or 20 is common but 16 is acknowledged to be young – and is, true to nature, a difficult wife. She makes her own demands and often gets her way, but only once she has proven to have keen business acumen that benefits her husband and his friends, though it makes her enemies among the other women she works with.

Elena, meanwhile, has a few serious boyfriends, but marriage is something for the future, when her studies are ended. She flirts with socialism, even Communism, but is it the social equality she craves or the personal freedoms? Education has given her choices that none of the girls back home have, but she is still limited to the few professions approved for women in 1960s Italy.

All this is written with the same thoughtful prose as the first volume. It’s not a small book, but there are no long flowery passages, no dwelling on politics or culture. It’s simply the minutely told story of two women and everyone in their lives, but particularly the story of Lila, and how Elena tries gradually to understand her friend and how their lives diverged.

“It’s Lila who makes writing difficult. My life forces me to imagine what hers would have been if what happened to me had happened to her, what use she would have made of my luck. And her life continuously appears in mine, in the words that I’ve uttered, in which there’s often an echo of hers, in a particular gesture that is an adaptation of a gesture of hers, in my less which is such because of her more, in my more which is the yielding to the force of her less. Not to mention what she never said but let me guess, what I didn’t know and read later in her notebooks. Thus the story of the facts has to reckon with the filters, deferments, partial truths, half lies: from it comes an arduous measurement of time passed that is based completely on the unreliable measuring device of words.”

Storia del nuovo cognome published 2012 by Edizioni E/O.

This translation published 2013 by Europa Editions.

Source: Christmas present from my Dad.