The archaeological pace had grown feverish

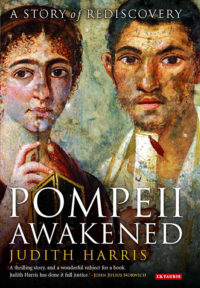

Pompeii Awakened

Pompeii Awakened

by Judith Harris

When Tim and I visited Pompeii last year our one disappointment was the lack of information at the excavations site. Even armed with the official guide book, we were confused about what some buildings were and which bits had been reconstructed. Though don’t get me wrong: we still loved it so much that we spent a second day there rather than climbing Vesuvius as originally planned.

So when we got home I searched for a book not about Pompeii pre-AD 79, but about the rediscovery of the town since 1748. Harris tracks the uncovering of Herculaneum and Pompeii up to the present day – a story that encompasses much of the political history of Europe over the same years and the development of modern archaeology.

This book is really good and definitely helped me to understand more of what we had seen in Pompeii, though I must admit it didn’t answer every question. It is packed with fascinating tidbits that I kept storing up to tell Tim.

What Harris makes abundantly clear is that the history of the rediscovery of Pompeii and Herculaneum is heavily affected at every stage by who was ruling the Naples region – a situation that changed frequently. She also details how destructive the early excavations were. The first digs were funded by the local royal family and they ordered the workmen to strip out everything that looked valuable, without any record being kept of what was taken from where. Tunnels were dug in straight lines straight through ancient walls and then filled back in with dirt. It’s quite upsetting.

These excavated artefacts were given as gifts to visiting dignitaries; sold to raise funds for the royal family (or equally often privately sold by whichever friend of the royal family was put in charge of the excavations); and stolen as the spoils of war. As such they were dispersed around the world. Some items have since been returned to Italy’s museums, primarily the National Archaeological Museum of Naples (which we visited the day before Pompeii) and some are still being studied in universities using methods that just weren’t available hundreds of years ago.

“As the archaeological pace had grown feverish, [chief engineer] Alcubierre opened possible sites further afield. Two hundred prison convicts and slaves from Tunisia and elsewhere in North Africa, watched at gunpoint by soldiers, were dragged to the sites to dig new tunnels, their clanking chains a rude counterpoint to the refined gossip of the Neapolitan courtiers…They soon struck the tiles of collapsed roofs beneath a scanty few feet of ash and lapillae, quite unlike the seventy feet of rocky covering Herculaneum. As work proceeded, streets could be made out.”

The story isn’t quite told chronologically – Harris concentrates on subjects rather than time periods, but arranged so that it’s still roughly in order. This does result in some repetition, and not just in separate chapters (I wonder if some sections of text were moved around). But that didn’t stop this being the most readable historical non-fiction I’ve tried.

I particularly enjoyed the sections about the scrolls from the library at Herculaneum, which Harris identifies as possibly the most historically important of all the archaeological finds. The scrolls that have been transcribed so far are in ancient Greek and the choice of philosophers’ works found can be used to interpret which Roman scholars visited and studied at the library. Unfortunately, many of the scrolls were destroyed in early attempts to unroll them, while others have been lost and still more were cut into strips that are still being pieced back together more than 200 years later. Other libraries of this era that have been found since have had one room of Greek texts and one room of Latin, so some scholars still hope to find another whole room of scrolls at Herculaneum.

“Attempting an alchemical opening of the scrolls, the [Duke of Sansevero] soaked several in a pot of mercury. The scrolls dissolved. Next a Neapolitan philologist…tucked a scroll inside a glass bell jar in brilliant sunshine and waited. The writing vanished altogether. A third improvised expert advised dunking the charred scrolls in oil or alternatively in boiling water, then leaving them to unroll by themselves in a damp basement…they rotted…Countless had been destroyed by benighted attempts to open the scrolls with a knife.”

And that is one of the frustrating and wonderful things about the Vesuvian towns: they are still being unearthed and interpreted. New methods let us learn more with less destruction, for instance using X-rays or other wavelengths of light to read text on heavily damaged walls or parchment. But the more of Pompeii that is dug up, the more that is then left exposed to the elements (and tourists) after thousands of years of protection under layers of ash, dirt and rubble. The buildings discovered more recently look fresher and newer, but that’s not just because of modern archaeology. Sunlight fades paint and tiles; wind and rain eat away at stone; plants embed themselves in nooks and cracks.

On our visit to Pompeii, large sections of the site were cordoned off. Sometimes this was new areas being unearthed; some was restoration; some was making safe areas that had become unstable; some was removing earlier attempts at renovation that are now considered “inaccurate”. During our visit I found it a little frustrating, but after reading this book I have sympathy.

In the four months since our visit, multiple new discoveries made at and about Pompeii have been revealed. The estimated date of the eruption in 79 AD has been revised. The manner in which hundreds of people died has been revisited. New skeletons, frescoes and statues are still being dug up. No book about Pompeii can ever be complete, at least not within the next few lifetimes.

Published 2007 by I B Taurus & Co.

Source: Christmas present from my Dad.