The heroin, that trickster, had made her feel actual love and then ripped it away

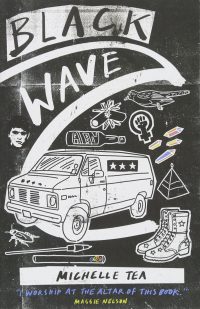

Black Wave

Black Wave

by Michelle Tea

This is an apocalyptic feminist novel about queer culture in 1990s California. It is strange and dark and brilliant. Perhaps it’s because it gets very meta, which I tend to enjoy.

Michelle Tea has novelised a period in her own life, when her life in San Francisco sunk to such a bad place that she felt her only way out was to move to LA. But that move doesn’t happen until halfway through the book, so the first half depicts her falling apart. It’s not a pretty story but Tea’s prose is funny enough that it manages to avoid being depressing.

Fictional Michelle’s main (though not only) problem is drugs. In the opening chapter we learn that, since writing a memoir that “glamorised her recreational drug intake”, Michelle has continued to party in San Francisco’s Mission neighbourhood, almost every night moving from alcohol to cocaine to alcohol to cannabis. She has balanced this with a job at a bookstore and a steady girlfriend to whom she is frequently unfaithful. She is at the centre of a subculture that she herself epitomises.

“On the stage the young queer seemed to know she was killing it. Michelle’s heart tore open and wept blood at the humanity of this girl’s experience. To be a butch girl in high school, to be better at masculinity than all the men around you, and to be punished for it! How everyone acts like you’re a freak when really you are the hottest most amazing gorgeous together deep creative creature the school has ever housed and…everyone knows it, and no-one can deal with it – oh, the head fuck of that situation, sitting on the shoulders of a teenager!”

But in 1999 it starts to change, the precarious balancing act begins to topple. Her drug use extends to crack and heroin. Her love life gets messier. Her finances are stretched so thin that one mis-step or piece of bad luck will cause it all to come crashing down.

And so she finds herself having to leave her beloved apartment, populated with alternative young ladies like herself, all hand-picked by Michelle as sympathetic to her lifestyle. She needs a fresh start and her brother is in LA, so it’s as good a place as any to go cold turkey on a failing relationship, drugs and alcohol.

“Everything was stupid. The heroin, that trickster, had made her feel actual love and then ripped it away, leaving her seratonin at low tide, her stomach nauseous, her pallor unattractive…Michelle was embarrassed at how quickly the simplest person could fascinate her. One pretty feature – and really, who doesn’t have at least one pretty feature? – and she was off, a romantic narrative spinning hay to gold, eking out a nobility, a deep sense of profundity out of your average drunk, fuckup, has-been, never-will-be.”

Or is that what happens? Because here the narrative flips between “Michelle Tomasik” (which turns out to be Tea’s actual name) who has moved to LA alone and whose arrival in LA coincides with the start of the apocalypse – yes, the actual end of the world – and another Michelle who is writing a metafiction about her own life, who moved to LA with a girlfriend who doesn’t want to be in this novel. Through a few confusing soul-searching chapters, it appears that when Michelle and her then partner moved to LA it marked the start of a several-years-long decline that is still difficult for Michelle to write about more than a decade later. So she writes about a metaphor for that relationship instead.

The apocalypse as depicted here has actually been seeded in the novel since the start. The sea is too toxic to bathe in, many birds and animals are extinct, the heat most days is unbearable. These clues are hidden at first among Michelle’s antics, her comedic perspective on the queer grunge culture she is part of. But in the second half of the novel the apocalypse comes to the fore. There are some descriptions of mass suicides that are so jaw-dropping, they are almost too shocking to be upsetting (for me – I fully expect these scenes will be super upsetting for some readers).

It is a real skill to turn intense sorrow and self-examination into a fun, often exciting work of fiction. Tea has a chatty style and sarcastic turn of phrase. Even in fictional Michelle’s nastiest and most selfish moments, she’s still an entertaining lead character.

Tea really did write her first fictionalised memoir in the 1990s while living in San Francisco, and has been writing ever since. I am definitely intrigued to check out some of her earlier work.

First published 2016 by the Feminist Press, New York.

Source: I subscribe to the book’s UK publisher, And Other Stories.