The muddy afternoon sky disgorged a white moon for teatime

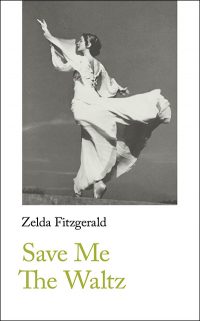

Save Me the Waltz

Save Me the Waltz

by Zelda Fitzgerald

A few years ago I read Z: a Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald by Therese Anne Fowler and became duly fascinated by this woman who was so much more than the wife of a famous writer. I was particularly interested to learn that Zelda too had written a novel but it was out of print at the time. Thank goodness for small publisher Handheld Press, which republished it in 2019.

This novel is based on Zelda’s own life from her teens through to her early 30s. It was written fast, over six weeks, which perhaps adds to the jazz-like atmosphere. Not that there is that much of it about partying hard in 1920s New York, nor much internal monologue. But there is a lot of exuberance in the language, riffs of evocative description breaking into the narrative. Which is a style that is initially a little tough-going and honestly I wasn’t sure I liked it at all, but it grew on me as the story progressed (though if I had been her editor I would have reined it in, at least in the earlier chapters).

The story begins – as Zelda’s life did – in Alabama, where Judge Austin Beggs and his wife Millie are raising three daughters. The older two are married off in quick succession, leaving the youngest, Alabama, alone to flirt with all the soldiers who descend on the town in 1917 and 1918. One of these is David Knight, an aspiring artist who comes back to Alabama to marry her as soon as he starts making money after the war.

“The muddy afternoon sky disgorged a white moon for teatime. It lay wedged in a split in the clouds like the wheel of a gun carriage in a rutted, deserted field of battle, slender, and tender and new after the storm. The brownstone apartment was swarming with people; the odour of cinnamon toast embalmed the entry.”

The Knights’ life together in New York is a whirlwind of socialising, drinking and fashion. They are spending money faster than David can earn it, even though he is a great success as a painter, so they decide to move to Connecticut, where they hope David will work more and they will spend less. But they have a daughter, Bonnie, and friends keep coming to stay with them for several-day-long parties, so the drinking and the money problems are as bad as ever. (This section is what I remember most clearly from the Fowler novel and the Amazon TV show based on it.) They decide the solution is to go to Europe.

On the French Riviera, life is initially perfect. They soon find themselves an international group of ex-pats to party with, a suitable nanny for Bonnie and their life settles into a daily pattern. And that’s where the problems begin. David is actually devoting time to his painting and Alabama is bored. Then the extramarital flirtations and the fights begin. (This part of the Fitzgeralds’ real life formed the start of F Scott’s novel Tender is the Night, so it was also familiar to me.)

“The post-war extravagance which had sent David and Alabama and some sixty thousand other Americans wandering over the face of Europe in a game of hare without hounds achieved its apex. The sword of Damocles, forged from the high hope of getting something for nothing and the demoralising expectation of getting nothing for something, was almost hung by the third of May.”

Recognising her own desperate need to find a passion to devote herself to, Alabama remembers how much she enjoyed dancing as a girl and begins ballet classes. Despite the relatively late-in-life start she works obsessively hard, with the goal to become a professional – she hopes that ballet will be her art and her living. The descriptions of her training are bloody and intense, and it is clear that Zelda is writing from experience.

Honestly, this is so closely based on her life that it is tough to assess it without feeling like I’m assessing Zelda’s actual life choices. While her husband’s alcoholism and her own mental health struggles are only hinted at in the novel, to a reader who knows a little about the famous couple it’s hard not to spot those hints. It certainly makes Alabama a more sympathetic character than she might otherwise be.

Besides the convoluted language, the one other problem I had reading this is the racism. While living in Connecticut, the Knights hire a Japanese butler, and the language referring to him almost made me stop reading. Thankfully that section is fairly short, but there are also moments of antisemitism and some not-at-all flattering national stereotypes. I know that this was written in 1932 but you would still hope that living and socialising with an international set would have prevented at least some of the slurs.

As a document of the Jazz Age from a woman’s perspective, this book is wonderful. As a novel, it’s…fine?

First published 1932 by Scribners.

Source: Storysmith, Bristol.