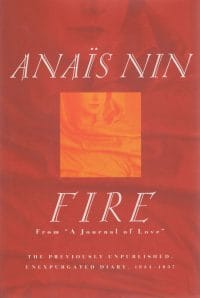

Book review: Fire: the Unexpurgated Diaries 1934–1937 by Anaïs Nin

I spent six months reading Fire: the Unexpurgated Diaries 1934–1937 by Anaïs Nin, which is just one volume of Nin’s massive collection of diaries. I kept the chunky tome on my bedside table, reading a few pages at a time. It took me a while (clearly) to get into the flow of it and I am still torn as to whether I want to hunt down the several other books that would complete the story.

I spent six months reading Fire: the Unexpurgated Diaries 1934–1937 by Anaïs Nin, which is just one volume of Nin’s massive collection of diaries. I kept the chunky tome on my bedside table, reading a few pages at a time. It took me a while (clearly) to get into the flow of it and I am still torn as to whether I want to hunt down the several other books that would complete the story.

This is not volume one (it’s books 48–52 of the hundreds of handwritten diaries Nin left behind). It’s not even the first part of the most famous trilogy of Nin’s diaries, known as A Journal of Love. But a loose note in the front of my smart hardback copy confirms that I ordered this from a secondhand book dealer in 2011, so I clearly wanted this specific volume and can only speculate that I had read a recommendation somewhere. I had read a few collections of Nin’s short stories and one of her novels, so I knew that I liked her writing. And her life is certainly a fascinating one to me.

Nin wrote diaries from a young age and edited her adult diaries for print during her own lifetime. Initially published from 1966 onwards, the first public versions of these books were cut heavily, removing all mention of her husband Hugh Guiler and several other of her more prominent lovers; changing names and details of other characters in her life. After the deaths of both Guiler and Nin, her long-term partner Rupert Pole took on the mammoth task of editing a new set of “unexpurgated” diaries, restoring those deleted details. His preface states “nothing of importance has been deleted”.

Obviously, this being Nin, this book is very sexually explicit (though I suspect that’s not what was cut first time round). It’s also probably worth knowing before you read this that she struggles with depression at times. Her mood swings wildly, and she acknowledges this. She is also unpredictable beyond her state of mental health. At times Nin will do everything she can to keep everyone she loves happy, pushing herself so hard it seems inevitable she will snap. But at other times she seems wilfully cold and cruel, refusing to acknowledge how her actions must affect her beloveds.

From the start, this diary is a whirlwind of friends, lovers and family, with plenty of musing on her marriage. It opens with Anaïs travelling to New York with her long-term lover Henry Miller (they had both lived in Paris for years by this point). Anaïs is seeking out the psychoanalyst Otto Rank, who had given her therapy previously and now suggests she could make some money by taking on her own patients. At this point Nin had only published one book herself and had used her own money to get Miller’s first book (Tropic of Cancer) published, which was not so far proving a wise investment financially speaking. So the promise of cash was welcome.

I found this first section of the diary the toughest going. Nin almost immediately begins affairs with Rank and multiple other men, constantly lying to Miller about her whereabouts. And then she is upset when Miller becomes distant and she suspects him of having his own affairs. But the really complicated lies begin when Guiler sails over from Paris to join her. She can no longer live with Miller but must still pay his rent, which she resents (fair enough).

“I am sad, I am sad, terribly sad, that there should be so many fissures and cracks in my life with Henry [Miller] that Huck [Otto Rank]’s strength should seep through and then invade. I feel imprisoned…True, with [Rank] I am most myself, but I also told him I was wistful the other day because I realized he was getting the natural, imperfect, selfish me, not the ideal me…We reached the conclusion that I could not destroy – that to create, it is necessary to destroy, that to create without destroying I nearly destroyed myself.”

I know diaries are inherently self-centred but I found Nin particularly narcissistic. Her journal entries at this point mention almost nothing besides her trysts with lovers, her justifications for the lies she tells, and more details about her therapy patients than seems ethical (though they at least remain anonymous). She also more than once, while in New York, states that women can’t be “true artists”, which angered me.

It picks up for me when she returns to Paris. She is writing more fluidly, seeing her friends and family, living life on her own terms. She officially lives with her husband but they appear to have an understanding that Anaïs is only home at the weekends. The rest of her time is split between her various lovers, though Miller gets the lion’s share – of both her time and her writing. Unlike Guiler, a banker who seems to just be grateful to have Nin in his life (they married in 1923 when she was 20 and very inexperienced, something she reflects back on towards the end of this book), Miller goes through jealous phases when Nin again brings out all her lies so that she can continue to freely live as she pleases.

But the really jealous character is the one who turns up halfway through this volume. Gonzalo Moré, like Nin, has Spanish and Latin American heritage and ignites in her a desire to rediscover that part of herself. Their love affair is intense in every sense, but after a few months he is yet another man whose rent and bills she is paying, complaining that his love for her is preventing him from his real calling of being a Communist revolutionary.

“It is true that because of my doubts and anxieties I only believe in fire. It is true that when I wrote the word “Fire” on this volume I did not know what I know today…That this is the story of my incendiary neurosis! I only believe in fire. My entire torture with Henry was due to doubt. It is doubt I am running away from. But now this mirage of Gonzalo takes on a warmer, lovelier body than other mirages…His immense tenderness, his hunger for love. I love to see him suffer because I know I can make him divinely happy.”

Interestingly, the Wikipedia page about Nin says that after leaving Spain aged 10 for the US, by the time she left high school she had forgotten how to speak Spanish (though was still fluent in French as well as English). So it’s notable that sections of this diary have been translated from both French and Spanish (indeed the odd phrase has been left in those languages, giving some flavour of Nin’s multilingual life). I’m curious whether “forgotten how to speak Spanish” is an exaggeration; if living in Paris for 10 years exposed her to enough Spanish speakers to restore her fluency; if it’s solely the relationship with Moré that rekindles her Spanish; or if the sections written in Spanish were riddled with errors. She comments at one point that she is maintaining three relationships in three languages (presumably French with Guiler, English with Miller and Spanish with Moré).

At least in Paris, there are glimpses of the world beyond sex. From 1936 onwards, the threat of war is looming – and indeed Spain is already at war with itself, which has a profound effect on Moré. Nin publishes her first novel, House of Incest, in 1936, which doesn’t bring in money but does attract attention from fellow writers. She muses at length on the difficulty of writing fiction at the same time as keeping up her diaries, and for long periods at a time chooses to edit the diaries rather than write new fiction. She also muses on the influence the men in her life have on her writing, and their attitudes towards it.

Nin’s writing seems to get more philosophical and descriptive as this book progresses, perhaps because it is becoming her only writing outlet at that point. The more florid and/or introspective sections reminded me of what I had liked about her novel and I think perhaps I would get on better reading the rest of her novels, rather than the rest of her diaries.

Published 1996 by Peter Owen Publishers.

Source: M D Hawkes